Explore the collection

Showing 68 items in the collection

68 items

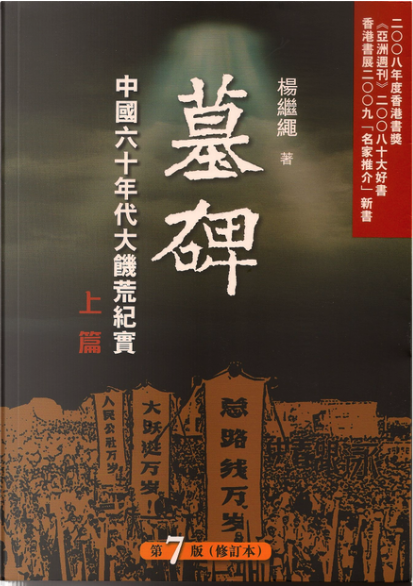

Book

Tombstone: The Great Chinese Famine, 1958-1962

The Great Famine in China in the 1960s was a rare famine in human history. From 1958 to 1962, according to incomplete statistics, 36 million people died of starvation in China; due to starvation the birthrate is estimated to have dropped to around 40 million. The number of people who died of starvation and the lowered birthrate due to starvation totaled more than 70 million, which is not only the largest number of deaths among all the disasters that occurred in China's history, but also the most painful and unprecedented tragedy in the history of mankind today. Was this a natural disaster or a man-made disaster? Officials deliberately covered it up and tried to minimize it, forbid any public discussion or expression about it. Yang Jisheng, a senior reporter of Xinhua News Agency, personally experienced the death of his father in the famine. Since then, he has devoted his heart and soul to this story. He has spent several years on it, running through a dozen or so provinces where the disaster was the most serious, and personally checking countless archives and records, both public and secret. He has interviewed the people involved and checked the evidence over and over again. Thus, he felt confident that he could, with the heart of the historical pen and the conscience of the news reporter, make a number of drafts, and truly recapture this tragic history of the human race and analyze the causes of this tragedy with a large amount of facts and data. With a wealth of facts and figures, he identifies the main cause of the famine as the totalitarian system. This is a book carries the collective memory of many ordinary Chinese people, and is a tombstone for the 36 million victims.

This book is published by Tiandi Books in Hong Kong. The English version of <i>Tombstone: The Great Chinese Famine, 1958-1962 </i> was translated by American author Stacy Mosher and can be purchased <a href= "https://www.amazon.com/Tombstone-Great-Chinese-Famine-1958-1962/dp/0374533997">here</a>.

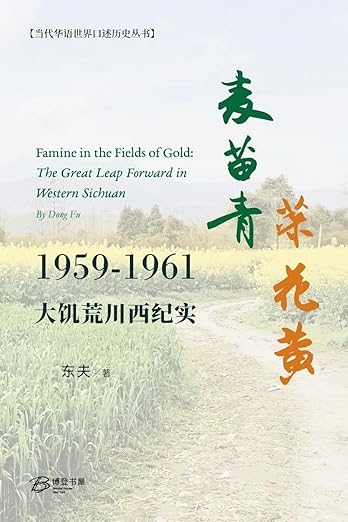

Book

Wheat Seedlings and Vegetable Blossoms: A Chronicle of the Great Famine in Western Sichuan Province

Traditionally, the western Sichuan plain was known as China's "Land of Abundance," but it became a focal point of the Great Famine of 1959-1961. Sichuan was one of the hardest-hit areas, with the largest number of deaths from starvation in the country and one of the highest death rates.

The title of the book, "Apricot Blossoms and Wheat Seedlings" is taken from a popular revolutionary song of the Mao era. In March, 1958, the Communist Party held a central work conference (known as the Chengdu Conference) at the Jinniu Dam Guest House near Chengdu, during which Mao Zedong inspected the Hongguang (Shining Red) Commune in nearby Pixian County. Two songs were written to commemorate that occasion.. One was "Red Flowers Bloom in the Shining Red Commune," and the other was "Apricot Blossoms and Wheat Seedlings."

The author of this book, Dong Fu (the pen name of Wang Dongyu), was born in Wenjiang, in the western Sichuan plains. He belonged to the "lao san jie"--students whose education was disrupted during the Cultural Revolution. His father was a veteran CCP cadre who engaged in underground party work and who later was responsible for economic policies. As a youth and as a soldier during the Great Leap Forward in Sichuan, Dong Fu saw the famine first-hand. During the Cultural Revolution he enlisted in the army and worked as a reporter for the Chengdu Military District's Zhanqi News.

After graduating from college, he began to work on this history. He was able to draw on his father's connections to research the book, in the 1980s and 1990s interviewing retired officials who knew his father and who could confide in him. Many have since passed away, giving this book great historical value. He was also able to collect extensive material from historical archives, also in part due to his father's and his own personal connections to the region.

This book was published by the Tianyuan Bookstore in Hong Kong in 2008 on the 50th anniversary of the start of the famine (some historians date the famine from 1958-1962, others from 1959-1961). In contrast to macro accounts of the Great Famine, such as Yang Jisheng's “Tombstone” (https://main--minjian-danganguan.netlify.app/collection/%E6%9D%A8%E7%BB%A7%E7%BB%B3-%E2%80%93-%E5%A2%93%E7%A2%91%EF%BC%9A%E4%B8%AD%E5%9B%BD%E5%85%AD%E5%8D%81%E5%B9%B4%E4%BB%A3%E5%A4%A7%E9%A5%A5%E8%8D%92%E7%BA%AA%E5%AE%9E) or Frank Dikötter's

“Mao's Great Famine” (https://www.frankdikotter.com/books/maos-great-famine/), Dong Fu's work is a case study of the famine in one area. By focusing on the western plains around Chengdu, the author shows how Mao's policies destroyed agricultural life in even historically rich areas that in normal times are China's breadbaskets.

Another feature of this book is its writing style. In reviewing this book in 2009, the theorist Hu Ping notes that history writing in China was shaken up by William Manchester's “The Glory and the Dream”, which was published in China in 1979. It was a vividly written history of the United States between 1932 and 1972 that showed that history could be engaging and entertaining. Hu Ping sees Dong Fu's work as inspired by Manchester's work, giving a panoramic, deftly written account suitable for the general reader, but based on solid research. Dong Fu weaves in the top-level battles with ordinary people's views, as well as social and cultural history. He mines the archives for telling details, such as complaints that people filed with the government, witty jingles that they composed to express their pain, and folk traditions. Hu Ping, who also grew up in the same region around the same time, writes:

"During the years of the Great Leap Forward, I was in primary school and junior high school in Chengdu. Reading the relevant chapters of Dong Fu's book, I felt very close to it, and many people and events from that year came vividly to mind. This feeling is something I have never experienced when reading other books about the Great Leap Forward period—whether they are theory books, history books, or even literature books." (https://www.rfa.org/mandarin/zhuanlan/shuwenpingjian/huping-05062009153055.html)

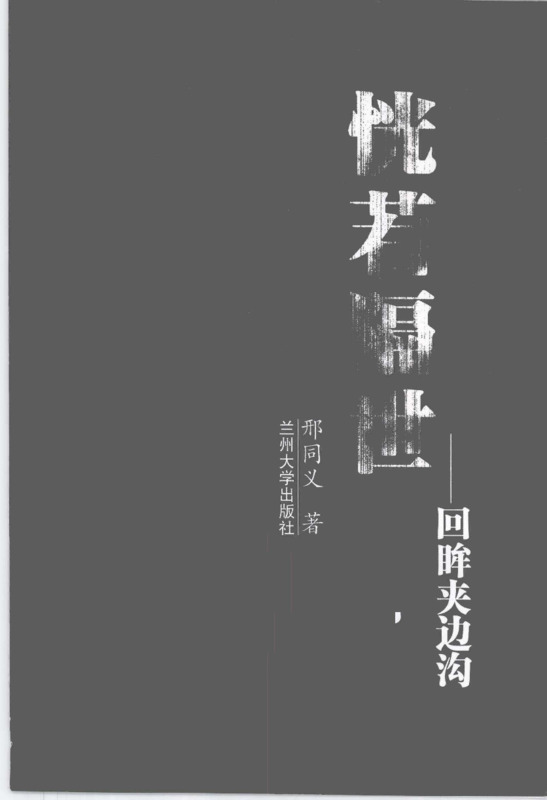

Book

Worlds Away: A Look Back at Jiabiangou

This book was published by Lanzhou University Press in 2004. The author, Xing Tongyi, once served as deputy director of Gansu People's Broadcasting Station and director of the Standing Committee of the Jiuquan Municipal People's Congress.

Jiabiangou Farm is a farm located on the edge of the Badain Jaran Desert in Jiuquan, Gansu Province, about 30 kilometers northeast of Jiuquan City. It became a labor camp in 1957. Before it was banned in October 1961, more than 3,000 intellectuals who were labeled as rightists were detained here. During the Great Famine, most of the intellectuals in farm labor camps died due to starvation and excessive workload. This is known as the Jiabiangou Incident. Jiabiangou has also become a symbol of the concentration camps where persecuted intellectuals were imprisoned.

Xing Tongyi was born in Tianshui, Gansu. He said that when he was young, he witnessed a neighbor named Guo being beaten as a rightist and sent to Jiabiangou Labor Camp. In 1961, he learned that this neighbor had starved to death in Jiabiangou. When he was in school at No. 1 Middle School in Tianshui City, his math teacher was Li Jinghang, a Christian who survived Jiabiangou. Xing Tongyi later served as a reporter and deputy director of Gansu Radio Station for a long time, and went to work in Jiuquan in 1996. After that, he took advantage of various opportunities to go deep into Jiabiangou and some surrounding labor reform farms. By consulting a large number of historical materials, he interviewed dozens of rightists who had undergone labor reform in Jiabiangou, or the children of these rightists. It took eight years to complete this book.

Unlike Yang Xianhui's novelistic description of Jiabiangou, Xing Tongyi's narrative is composed of interviews with the people involved and quotations from first-hand historical materials. According to Xing Tongyi, the historical materials he referred to include the Jiabiangou Farm's "Plan and Mission Statement" and the anti-rightist report of "Gansu Daily" in 1957. In addition to interviewing Jiabiangou survivors or their children, he also found information on more than 40 of the more than 2,000 rightists who were in labor camps at the time and were prosecuted by the Jiuquan County Procuratorate for resisting labor camps. After the book was published, people continued to provide him with historical materials, such as death notices and diaries of the victims.

How many labor camp inmates were there in Jiabiangou at that time? In order to clarify this issue, Xing Tongyi interviewed dozens of people, reviewed information, and also found Luo Zengfu, the production section chief of Jiabiangou Labor Camp, the only farm management cadre alive at the time. Based on the information provided by Luo Zengfu, Xing Tongyi's research concluded that there were a total of about 2,800 inmates in Jiabiangou Farm at that time, including about 2,500 rightists. This number is considered to be relatively accurate.

Article

Wuhan Diary

This collection of diary entries by Wuhan-based filmmaker and activist Ai Xiaoming showcases her life during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, from February to March 2020. In these diary entries, Ai shares the daily challenges which many Chinese people grappled with, as well as their hopes and questions for the government and Chinese society at large. Her diary also examines problems regarding the expanding powers of the Chinese government. The first entry of Ai’s diary was published in English by the New Left Review, which can be found here:

https://newleftreview.org/issues/ii122/articles/xiaoming-ai-wuhan-diary.

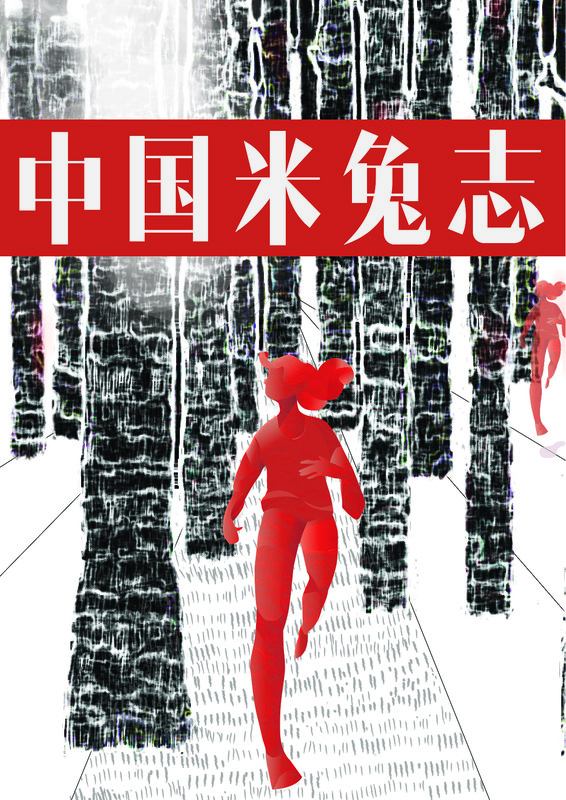

图书

#MeToo in China Archives 2018.1-2019.7

On New Year's Day 2018, Beihang University graduate Luo Xixi took the lead in breaking China's silence on the issue of sexual harassment when she publicly reported on social media that Beihang professor Chen Xiaowu had sexually harassed her. This was the first major event in China’s #Metoo movement, which has since spread from colleges and universities to other fields. #Metoo provoked an unprecedented discussion in China, and the issues of feminism and sexual harassment attracted a rare and widespread attention, with a variety of complaints, comments, studies, and advocacy articles springing up all over the internet.

<i>#MeToo in China Archives 2018.1-2019.7</i> is a compilation of sexual harassment-related articles written between January 2018 and July 2019. This archive is massive, totaling more than 2,500 pages, and is divided into three main volumes: “#Metoo in Higher Education”, “#Metoo in other fields”, and “#Metoo discussions’. Volume I and Volume II consist of individual #Metoo cases, arranged in chronological order. Articles in volume 3 can be broadly categorized into general reviews, investigative reports, personal stories, advocacy and activism, tools and resources,etc. During the #Metoo movement, many liberal public intellectuals questioned the movement, likening it to big-character posters during the Hundred Flowers campaign, and arguing that it might lead to the proliferation of wrongful convictions. It triggered heated debates, and this archive also contains a number of related articles.

The process of compiling this archive itself became an act of resistance, given the severe repression on freedom of expression and social movements. The editorial team faced tremendous challenges in collecting articles that had been deleted or published as images to bypass online censorship. It spent a great deal of time and personnel piecing together scraps of information and transcribing words in images. Reading traumatic personal stories - including those about the hardships in seeking remedies - caused psychological trauma for the editors themselves.

Nevertheless, #Metoo has also a process of collective healing, in which women with shared experiences saw each other, realized the structural problems behind sexual violence, and gained the strength to move on and push for change. Finally, during the compilation process, the editorial team also benefited from archiving efforts made by other websites and individuals, demonstrating that the rescue and preservation of people’s history is a collective and collaborative task.

This archive is published on https://chinesefeminism.org/.

Article

A Brief History of Young Feminists Activism in China

Since 2012, a group known as the “Young Feminist Activists”, has emerged in China. They often use performance art in public to promote gender equality issues; they question injustice, and engage in policy advocacy to advance women’s rights. They make use of social media and the internet to provoke public debate, build public support, and mount pressure for social and self-transformation in China. Their direct actions created new space for activism in China's tightening political environment.

This article provides a detailed overview of the actions initiated by the young feminist activists between 2012 and 2019. These actions cover a wide range of gender issues, including but not limited to sexual assault/harassment, gender-based violence, gender equality in employment and schooling, gender stigma and stereotyping, marriage autonomy, and lesbian rights and interests. These actions have not only raised the public's awareness of gender equality, but also promoted the introduction of gender equality legislation and policies.

A turning point came In 2015 when five young feminist activists were arrested and detained for 37 days for planning to hold an anti-sexual harassment campaign on March 8, Interantional Women's Day. Since then, young feminist activists have almost completely lost their space on the streets. However, as can be seen from this article, feminist activism did not disappear, but sustained and continued in a variety of ways, including the creative use of social media and leveraging transnational solidarity and action.

In the article, the author says, “Young feminist activists should not be forgotten by the public, especially in an environment where censorship has intensified in the past years, civil society has nearly collapsed, and it is extremely difficult for people to speak out. While there is a seeming increase in discussion of feminism in domestic social media, it has been severely depoliticized, feminist activists are marginalized and stigmatized, and their voices silenced. Therefore, it is particularly important to tell the stories of young feminist activists and popularize knowledge about the domestic feminist movement. It is important to let more people see the spirit and achievements of the new generation of Chinese feminists, and understand the important gender issues they have promoted.”

The article is accompanied by numerous images, videos and links to other resources for further reading.

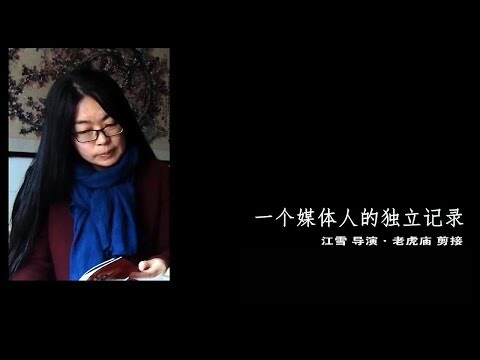

Film and Video

Zhang Zhan Video Series of COVID-19 Outbreak in Wuhan

On 23 January 2020, the Chinese government imposed a lockdown in Wuhan. On February 1, Zhang Zhan took a train from Shanghai to Wuhan. From then until her arrest by the Shanghai police on May 14, Zhang Zhan continued to document the situation in Wuhan on video at the frontline of the pandemic. On February 7, she launched a YouTube channel under her real name and released her first video, “Claiming the Right to Freedom of Expression,” in memory of Dr. Li Wenliang and in solidarity with citizen journalists Chen Qiusi and Fang Bin, who had been taken away for reporting on COVID-19. She said in the video: “If Chinese citizens still do not have the right to freedom of expression,then we are all Li Wenliang." On the same day, Zhang Zhan received a phone call from Shanghai's state security agency threatening to quarantine her if she continued to speak out online, but she did not give in. By the time she was arrested, Zhang Zhan had posted 122 videos on <a href=”https://www.youtube.com/@%E5%BC%A0%E5%B1%95-y3p/featured”>her YouTube channel</a>. In her videos, she traveled around Wuhan at the height of COVID-19, documenting empty streets, the roar of funeral home incinerators late at night, the desperation of patients with no place to turn for medical care, the arbitrary deprivation of residents’ freedom of movement, and the chaotic and hypocritical nature of government policies. These videos show the world the reality of Wuhan in the early days of the outbreak, making thema precious historical record.