Over the past five years, Hong Kong’s news industry has faced increasing restrictions, ending what had been one of the liveliest Sinophone media scenes in the world. Nowhere is that more evident than in how the territory’s media covers commemorations of the June 4, 1989, Tiananmen Square Massacre.

Nowadays, addressing this topic demands considerable courage. But for two decades following 1989, reporting on Tiananmen was an annual event each spring and summer that shaped a generation of Hong Kong journalists.

The centrality of Tiananmen to Hong Kong’s media goes back to the spring and summer of 1989. In Beijing, Hong Kong journalists formed a distinct presence in Tiananmen Square and among the crowds. They were unlike their Mainland Chinese counterparts, who operated under numerous constraints and could only find limited space for expression. Hong Kong journalists also differed from Western media reporters, who were essentially covering a distant foreign story. Sharing the same ethnicity as the students, Hong Kong journalists viewed this student movement not merely as a subject for reporting but as a matter deeply personal to them.

The People Will Not Forget: A Chronicle by 64 Hong Kong Reporters, written by Hong Kong journalists who traveled to Beijing to cover the student movement, directly captures their internal conflict as both news professionals and individuals of Chinese ethnicity: “At such a crucial juncture concerning the nation’s future and fundamental principles, how could we possibly remain detached and calm?”

At that time, Hong Kong was still a British colony, yet Hong Kong journalists deeply understood that the fate of this student movement was inextricably linked to the future of the Hong Kong press and Hong Kong itself.

Witnessing and Remembering

It is now hard to imagine the intense dedication Hong Kong journalists had towards reporting on the 1989 student movement in Beijing. The People Will Not Forget recounts that beyond those officially sent by Hong Kong media organizations, many journalists “paid for their own trips, defying family wishes and newsroom bans, to rush to Beijing as ‘witnesses to history.’” These self-funded journalists numbered in the dozens at their peak.

In Beijing, the collective gaze of hundreds of Hong Kong journalists witnessed pivotal historical moments, encompassing both exhilarating highs and terrifying lows. They not only documented these scenes through text, radio, and television but also continuously recalled and recounted them in the three decades that followed. It is this initial documentation and subsequent remembrance that largely cemented June Fourth as a lasting concern and a collective memory for all of Hong Kong.

Choi Suk Fong, then a journalist for Sing Tao Daily, was the last Hong Kong reporter to leave Tiananmen Square, even writing a will while there. She later published Living Monument in the Square: June 4 Bloodshed through the Eyes of a Hong Kong Woman Reporter, a compilation of her interviews and subsequent reflections. The metaphor of a “living monument” aptly encapsulates the significance of Hong Kong journalists as a collective.

Notably, Living Monument in the Square includes not only interviews with student leaders and intellectuals but also a dedicated section on approximately two thousand grassroots individuals involved in the movement. While some remained nameless and most were only briefly mentioned, this still constitutes a precious record. It demonstrates that this movement was a genuine mass democratic movement, not simply students and intellectuals “stirring trouble.” Moreover, these ordinary citizens likely paid a far greater price than the student leaders. Ensuring they are not forgotten by history is a crucial contribution of Living Monument in the Square.

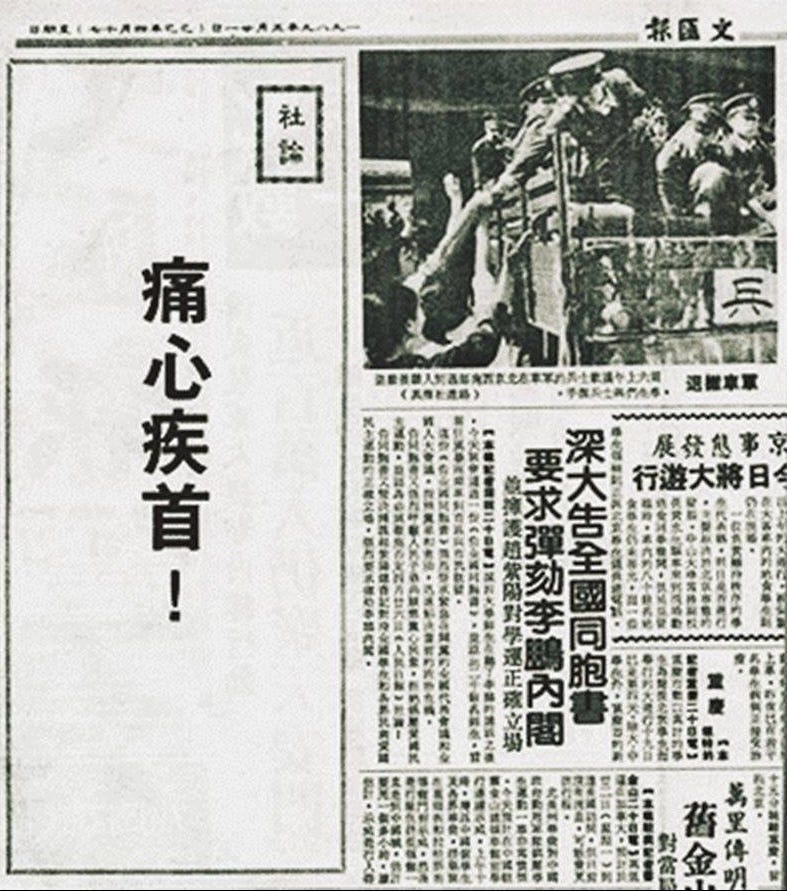

On May 21, 1989, Hong Kong’s Wen Wei Po published an editorial with a blank space that only stated, “Deep Grief,” protesting the Chinese government’s martial law decree.

On May 21, 1989, Hong Kong’s Wen Wei Po published an editorial with a blank space that only stated, “Deep Grief,” protesting the Chinese government’s martial law decree.

Humanity Versus Party Loyalty

Hong Kong journalists were not just recording history; they were living through it. Following the Tiananmen Square crackdown, they had to leave Beijing swiftly for their own safety. During this tense period, many instances of human compassion emerged, glimpses of which we gain through the journalists’ later narratives.

For example, in The People Will Not Forget, Joseph Tse, then an ATV reporter, frequently recalled his escape from Beijing. On June 5, 1989, he and his colleagues were driving to the airport when they were stopped by hundreds of people blocking the road. The crowd asked, “Who are you?” Tse nervously replied truthfully, “Hong Kong reporters.” They then asked, “Did you see what happened in the square?” Tse answered, “We saw everything.”

What followed was not detention or punishment, but rather, the crowd approached the ATV reporters and said, “You must get the news out as quickly as possible! We’ll clear a path for you!”

At the airport, the shaken group faced questioning from customs: “Are you journalists?” Tse bravely answered, “Yes.” The customs officer asked, “Do you have any on-site video footage?” Tse truthfully replied, “Yes.”

Upon learning their identities, the customs official did not confiscate their video tapes. Instead, after a moment of silence, he said, “Go quickly!”

In an era before the Internet, all interview materials had to be physically transported. At the Beijing Airport at that time, many individuals quietly assisted journalists in getting their materials overseas. Numerous ordinary passengers participated in this effort, driven by the shared desire to ensure these facts were seen and preserved in history.

The involvement of editors and reporters from Mainland Chinese party newspapers, including the People’s Daily, in the movement demonstrated their agency as citizens, rather than the expected loyalty of news professionals to the regime. Similarly, Wen Wei Po, a Hong Kong newspaper also under Communist Party leadership, displayed a comparable spirit. As evident in Bloodshed in Beijing and China: Hong Kong Wen Wei Bao 1989 Special Edition, Wen Wei Po reporters conducted on-site interviews in Beijing, amassing extensive visual and textual documentation that truthfully recorded the movement’s progression and the brutality of the crackdown—a clear contradiction of the Communist Party’s propaganda directives.

In fact, as early as May 21, 1989, Wen Wei Po responded to the imposition of martial law by publishing an editorial with a blank space, featuring only the large characters stating, “Deep Grief.” Lee Tze Chung, the newspaper’s publisher, Kam Yiu-yu, the editor-in-chief, and Ching Cheong, the deputy editor-in-chief, were subsequently dismissed, and approximately thirty other employees resigned in support of Lee.

Truth and Ethics

In recounting the June Fourth Incident, many Hong Kong journalists frequently emphasize the event’s complexity and the opacity of Chinese Communist Party politics. Consequently, no one could claim to possess the complete truth; the only recourse was to faithfully record their direct observations and testimonies, hoping that the eventual aggregation of more information would lead to a closer understanding of the truth.

In The People Will Not Forget, the journalists also listed and reflected on some of the false information that circulated at the time (such as reports of Li Peng’s resignation and Deng Xiaoping’s alleged poisoning). This demonstrates that while the journalists held strong personal views on the events, they understood the importance of adhering to professional ethics in their work.

The journalists attributed the media’s misreporting of false information to market competition. Furthermore, they raised another crucial point of reflection: how should journalists conduct themselves during such a social movement?

The book states: “As students moved from campuses to the streets, staging numerous marches, Beijing intellectuals actively responded, and public sentiment surged. Journalists were also affected. When the marching columns passed by, journalists instinctively raised ‘V’ signs in salute or dropped money into the students’ donation boxes. This later evolved into providing newspapers to students to share outside information, or even personally paying for students’ meals and offering them cigarettes, forging friendships with them.

“During the student hunger strike sit-in in Tiananmen Square on May 13, and throughout the subsequent period of martial law, Hong Kong journalists almost universally sided with the students and intellectuals. Some journalists invited students who had been holding out in the square for days to their hotel rooms to shower and change clothes; others lent their rooms to student leaders for meetings or rest. Some even offered advice and developed close relationships with their interview subjects.”

While this transcending of the traditional journalistic role could be seen as a natural response to the circumstances, it also prompted journalists committed to professionalism to exercise caution and reflect on their actions.

Choi Suk Fong offered a similar reflection in Living Monument in the Square: “As a journalist from Hong Kong, I was warmly invited to join the marching columns and received protection from the students. When I entered the demonstration site with the crowd under the banners of ‘freedom of the press’ and ‘speak the truth’ of the capital’s press circles, I already realized that I could neither detach myself from the scene nor naturally avoid becoming involved in their actions. My role blurred between directly participating in the event as a marcher and adhering to objective and impartial reporting as a journalist. Perhaps, in that specific historical moment, in that powerful current of the times, this merging of roles was unavoidable, making it difficult to remain detached and coldly observe the unfolding events.”

These firsthand accounts of journalists’ experiences offer invaluable historical material, revealing the inherent tensions often faced by those in any part of the world who document history. Recorders cannot divorce themselves entirely from the context, adopting a purely detached perspective, especially when the events unfolding involve fundamental issues of human life and national destiny. The key lies not in feigning detachment but in being self-aware of one’s position while immersed in the events—these reflections represent an additional and profound contribution of Hong Kong journalists’ records and memories of June Fourth.